What significance does meditation have in the everyday life of a Buddhist? And what does meditation actually mean?

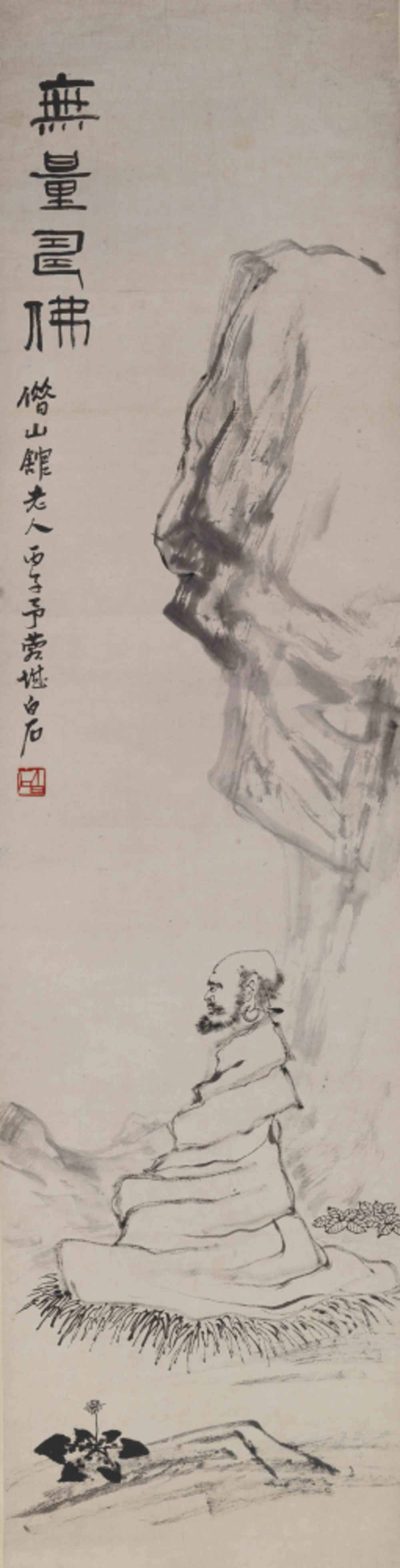

The boundary between meditation and ritual is often difficult to draw. Meditative practices tend to vary greatly, depending on which school of Buddhism we are talking about.

Early Buddhist texts refer to meditation as a means of gaining control over the senses. Its aim is to prepare followers to recognize true reality, unclouded by false assumptions.

For a long time, the exercises were performed only by monks and nuns.

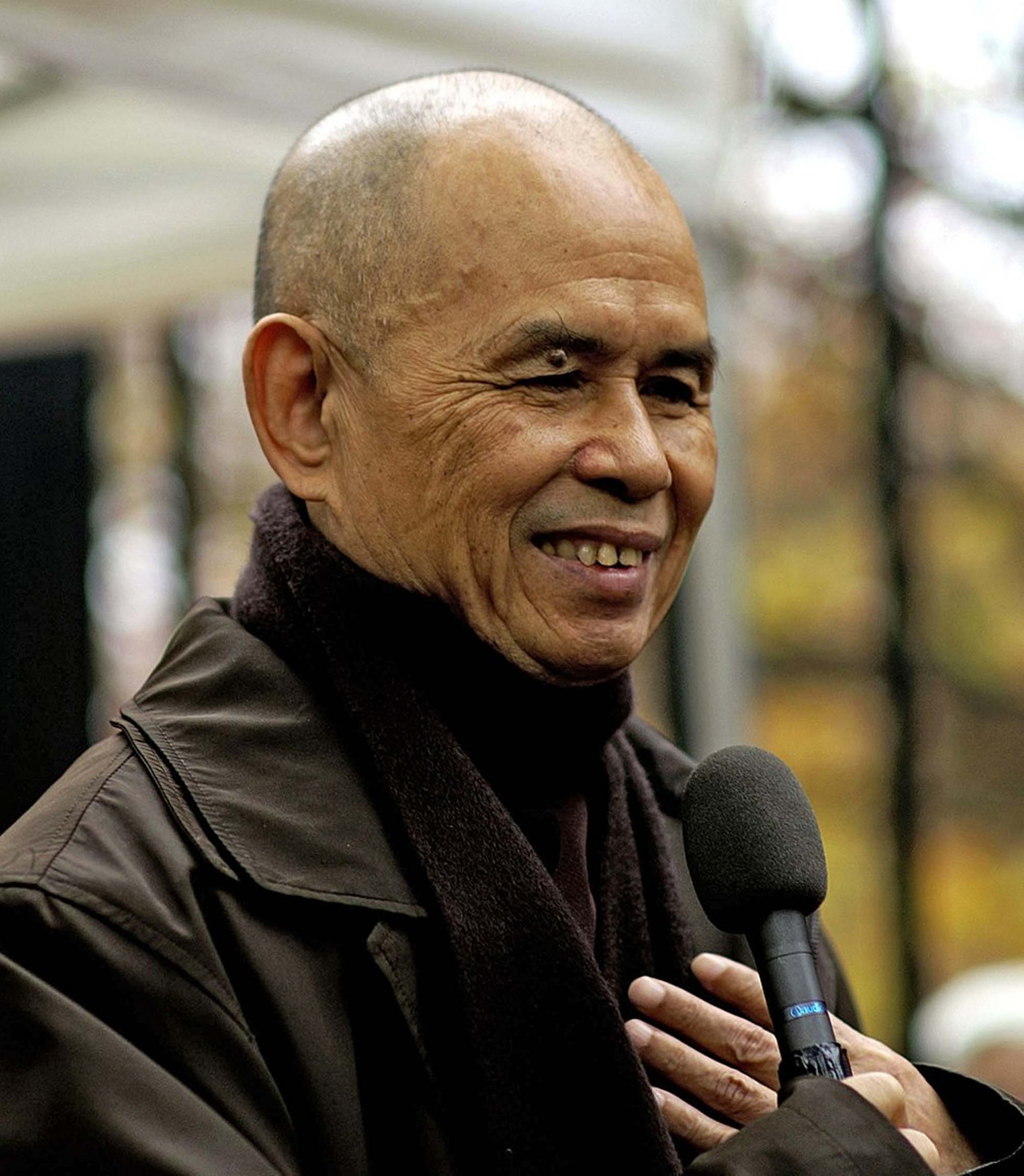

Meditation did not become a common practice for laypeople until the 20th century. Today meditation is practised in order to change one’s approach to life, attain a better quality of life, or boost one’s sense of well-being. These are very recent goals and point to a new way of understanding this old religious practice.

In this story you can explore what meditation means in the various Buddhist traditions.